- apparently "shall" can mean "may" in alabama. i did not know that. #

- a good reminder of the desirability of exclusion of consequentials clauses. at least for vendors. http://t.co/XcRJ5jNX #

- google delays nexus q. so that it will "do more". what a surprise. not. http://t.co/NA2IZV7D #

- amazon decides it needs music licenses for cloud player. curious what prompted the change of heart. http://t.co/WgoCPlTY #

- did not realize that samsung was outselling apple almost 2 to 1. http://t.co/etmCxZHR #

- a bit old. apparently using publishing apis reduces engagement by 70%. surprising. http://t.co/t9ZaNutv #

- print your own gun at home. well, more like gun parts. the important bits. a few legal implications, methinks. http://t.co/o48AWxUd #

what i thought big data was…

I read with interest an article in RWW entitled Big Data: What Do You Think It Is?.

I suppose the term “big data” is akin to “cloud computing” – you hear the term bandied about quite a bit, but often without a clear definition. Unless your talking about about legal presentations, in which you’ll see a zillion definitions of cloud computing trotted out, including, yes, once again, the NIST definition of cloud computing (PDF), amongst various others.

In any event, it was nice to see an article asking the question and (hopefully) providing a clear answer. Perhaps suprisingly (or not), when folks were surveyed on what they thought big data meant, there was no clear consensus:

Harris asked 154 C-level executives from U.S.-based multi-national companies last April a series of questions, one of them being to simply pick the definition of “Big Data” that most closely resembled their own strategies. The results were all over the map. While 28% of respondents agreed with “Massive growth of transaction data” (the notion that data is getting bigger) as most like their own concepts, 24% agreed with “New technologies designed to address the volume, variety, and velocity challenges of big data” (the notion that database systems are getting more complex). Some 19% agreed with the “requirement to store and archive data for regulatory and compliance,” 18% agreed with the “explosion of new data sources,” while 11% stuck with “Other.”

The author then goes on to attempt to create a generally aapplicable definition:

Essentially, Big Data tools address the way large quantities of data are stored, accessed and presented for manipulation or analysis.

Perhaps rightly or wrongly, that hasn’t quite been the impression I’ve had when reading articles about big data. I’m not at all suggesting that the proposed definition is incorrect. In fact, perhaps the opposite. That being said, when I have in the past seen the term “big data” it was almost always used to describe not the technologies used to store, access or data, but rather primarily (or almost exclusively) analysis of very large datasets in order to develop new knowledge, ideas or products. Or starting to collect that had previously not been collected (at least not in easily manipulated digital form) for the purposes of such analysis. For example, to figure out, based on purchasing patterns, that someone is pregnant in order to market baby supplies to them. Or using cell-phone records to detect disease outbreaks, analyzing listening data to figure out how a recording artist becomes a star, analyzing information collected from smart meters to figure out ways to reduce energy consumption, using algorithms to analyze server and device logs to manage IT infrastructure, etc. etc. – see a nice collection of stories in GigaOm.

Of course, all of that necessarily presumes that the technology exists to record and access such large datasets. So that may well be properly considered part of big data, I suppose. Thought perhaps not quite as interesting as what you can do with it. At least to me.

cloud provider certification not worth that much

Great story in The Register from the other side of the pond on the recent trend of cloud service providers, such as Amazon AWS, to undergo a “self-certification process” by submitting details regarding its security measures to the “Security, Trust & Assurance Registry (STAR), operated by not-for-profit body the Cloud Security Alliance (CSA).”

However, the UK Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), while welcoming the initiative, offered this somewhat ambivalent statement:

“While any scheme aimed at ensuring people’s information is adequately protected in line with an organisation’s requirements under the Act is to be welcomed, organisations thinking of using cloud service providers must understand that they are still responsible for the safety of that data. Just because their cloud service provider is registered with such a scheme, does not absolve the organisation who collected the data of their legal responsibilities.”

I don’t think this statement must necessarily be read, in a literal manner, to be tantamount to The Register’s headline that folks “can’t rely” on such certification. Rather, it just vague enough so that folks will have no idea the extent to which they may. Which I suppose may be the same thing. Alas.

Anyway, the ICO has promised to provide further guidance on storing personal information in the cloud in the autumn.

tweet digest for week ended 2012-07-29

- great read about us govt access to e-mail and stuff stored in the cloud. http://t.co/RSkdTPsa #

- experts manage to hack iris scanners. using genetic algorithms. how appropriate. http://t.co/JGQpkOh3 #

- neat. use hand (or finger) writing to google on your mobile device. http://t.co/nJot2vGO #

- wishful thinking that they'd come to canada. google fiber launches in kc. 1 gbps. nice. http://t.co/2QU5Ive4 #

- interesting comments from gabe newell. i'm a fan of him and valve. except steam. i hate steam. http://t.co/xcp7HMv2 #

- curious. craigslist sues service that maps its listings. not clear why. http://t.co/nTUgsAgN #

- surprised by the addition of tmo to the rwl deathwatch. thought they were a decent carrier. http://t.co/1fsBJr8f #

- scientists create self-propelling jellyfish from heart cells of a rat. http://t.co/5MQcroY3 i, for one, welcome.. ah forget it. #

- fascinating read on medical risks of being an astronaut. http://t.co/xkc0PjFa #

- hmm. apple presents for the first time at black hat. wish i was there. and at defcon. http://t.co/NIZOpXsL #

- surprising. first negative thing i've read about the nexus 7. apparently the display ain't so great. http://t.co/fEPbtiFO #

- oh the irony. zuckerberg awarded privacy patent. http://t.co/jmf9JPBH #

- incredible. first software sim of an entire organism. http://t.co/oa9aJpbr #

the paradox of diversification

I read an entry on Fred Wilson’s blog on The Power Of Diversification. I don’t disagree with anything in his column, or the earlier one he links to where he describes basic portfolio theory. But the concept of diversification has always puzzled me a bit. Taken to it’s conclusion, portfolio theory suggests that optimal investment is one that is extremely diversified across all investments – i.e. the market portfolio. That’s often the reason given to invest in market index funds (though optimally diversification should be across asset types that may not be reflected or inadequately reflected in market indices – e.g. bonds, real estate, precious metals, etc.). This is because diversification reduces the impact of company or investee specific risk. Going further, if one diversifies more broadly, you eliminate industry specific risk, geographic specific risk, and so on. Therefore, the optimal investment strategy to maximize your return for any given level of risk is to invest only in the market portfolio, then leverage or deleverage to meet your personal risk tolerance. I’m probably not explaining it all too well – try Wikipedia for a more detailed and better written explanation.

Diversification can be quite a powerful tool. In fact, in certain (rather limited) circumstances, it can even change two losing prospects into a winner, so long as you alternate between the two. Not really the subject of what I wanted to chat about today – you can read more about Parrondo’s Paradox in this NYT archive or on io9. Or just google it.

Anyway, the mention of paradox is fortuitous. I don’t necessarily know if it’s the right term for what I’m about to describe, or whether it really does precisely fit within the definition of paradox. Nonetheless, to me, it seems that advice on diversification seems somewhat paradoxical. And by that, I mean that if you follow the logical conclusion of the lesson taught by modern portfolio theory on diversification, then it doesn’t really make much sense for anyone to specialize say, for example, in early stage technology companies. The greater the departure from the market or efficient frontier portfolio, the less optimal the risk/return ratio. And yet, despite this, there are many, many specialists that take a narrow focus (despite their diversification amongst investee companies), just like Union Square Ventures, who often do quite well, even though portfolio theory suggests that all specialists are using sub-optimal strategies exposing them to more risk than they need to be exposed to for a given return.

I suppose the same could be said of entrepreneurs who, very often, put all their eggs into one basket – and, to address a point made by Fred Wilson, this is even after they’ve succeeded and accumulated a great deal of wealth. Elon Musk may be a good example of that. I think (but don’t know with certainty) that most of his wealth is invested in two, and only two, highly risky and focused ventures (being Tesla Motors and SpaceX).

Moreover, it would seem to me that if everyone in the world pursued the optimal diversification strategy as suggested by portfolio theory, including, for example, all narrowly focused or industry specific venture capital funds, then the diversity of assets (and possibly asset classes) would, I think diminish. Sort of like the paradox of efficient markets, I suppose.

But who knows. I don’t pretend to be an expert in modern portfolio theory. Would be interested in hearing from those more knowledgeable in the area.

open source legal documents

Just got a note from the docracy folks. They’ve developed a new, US oriented, open source mobile privacy policy.

I’m quite intrigued by the whole notion of open source legal documents. As some readers of this blog may know, I am very much a fan of open source technology. That being said, I do wonder whether the application of open source models to legal documents will yield the same benefits as their application to code.

I suppose it should, but must admit I do have some doubts. For example, I don’t think that open source legal agreements will necessarily result in widespread adoption or create standards the way open source software does, for a variety of reasons – e.g. differences in each jurisdiction’s laws, variations in business models, or variations in risk tolerance for users.

Moreover, I’m not necessarily sure open source legal agreements that are freely available will supplant professional legal services, the way, for example, that Linux has (or at least has the possibility) of supplanting operating systems for which license fees are paid and no source is made available – like Windows.

Why? Because legal services are already provided in a manner similar to one open source business model – that of value added services. While I certainly wouldn’t mind trying to exploit my drafting work by licensing forms of agreements at $X dollars a pop, that’s not typically how legal services work. When someone asks me to help them create a software license agreement, I’ll ask them various questions regarding their product, how they plan to license and distribute it, how they plan to charge for it, and so on, then take one or more existing precedents and start tailoring to their needs, charging by the hour to do that and perhaps to negotiate the terms from time to time. I don’t charge a license or usage fee for the use of the precedents, but rather only for the “value-add” services. It might be nice too, but if your competitors don’t (and I think most don’t) then it’s tough for you do so. Which is perhaps why legal services typically don’t scale quite as well as other industries.

Sorry, I digress. Anyway, my point was that this service model is quite similar to one approach to one open source business model – license the core product under an open source license, and sell value-add services, such as support, custom development, implementation services and the like – stuff that requires expertise for those that need it.

Just to be clear, I’m not suggesting that the concept of open source legal documents is bad (because it’s not), but rather that I can’t see it having the same impact on the legal services industry as open source code has had on the IT industry. But who knows.

who invented the internet

Had been planning just to tweet this now (someone old) story in the Wall Street Journal about Who Really Invented the Internet but thought I’d comment just a bit. The opinion piece is written by Gordon Crovitz, who seems to have some really solid, heavy-duty credentials – they make me look like a special needs student:

Gordon Crovitz is a media and information industry advisor and executive, including former publisher of The Wall Street Journal, executive vice president of Dow Jones and president of its Consumer Media Group. He has been active in digital media since the early 1990s, overseeing the growth of The Wall Street Journal Online to more than one million paying subscribers, making WSJ.com the largest paid news site on the Web. He launched the Factiva business-search service and led the acquisition for Dow Jones of the MarketWatch Web site, VentureOne database, Private Equity Analyst newsletter and online news services VentureWire (Silicon Valley), e-Financial News (London) and VWD (Frankfurt).

He is co-founder of Journalism Online, a member of the board of directors of ProQuest and Blurb and is on the board of advisors of several early-stage companies, including SocialMedian (sold to XING), UpCompany, Halogen Guides, YouNoodle, Peer39, SkyGrid, ExpertCEO and Clickability. He is an investor in Betaworks, a New York incubator for startups, and in Business Insider.

Earlier in his career, Gordon wrote the “Rule of Law” column for the Journal and won several awards including the Gerald Loeb Award for business commentary. He was editor and publisher of the Far Eastern Economic Review in Hong Kong and editorial-page editor of The Wall Street Journal Europe in Brussels.

He graduated from the University of Chicago and has law degrees from Wadham College, Oxford University, which he attended as a Rhodes scholar, and Yale Law School.

Wow.

Anyway, the premise of the article is that the US government didn’t create the internet:

It’s an urban legend that the government launched the Internet. The myth is that the Pentagon created the Internet to keep its communications lines up even in a nuclear strike. The truth is a more interesting story about how innovation happens—and about how hard it is to build successful technology companies even once the government gets out of the way.

Interesting premise, but quite surprised by some statements he makes in support of it which seem to be a bit inaccurate. Such as equating the invention of Ethernet with the invention of the internet. Or suggesting that the Ethernet was “developed to link different computer networks”.

Oops. Looks like others have already dissected this much more thoroughly. See Ars Technica and the LA Times.

fascinating nanotechnology

It’s been so long since I’ve read about any interesting developments in nanotechnology, apart from a few folks who’ve developed neat superhydrophobic coatings, which, although they’ll save your phone, or keep your clothes from getting dirty, won’t exactly save the world. So it was nice to read about the development of a “wonder material” (nanontubes) that has the potential to do things like purify water instantly or kill tumors by regulating substances inside of cells.

Well played, nanotech, well-played.

delicious (human-based) gelatin

I read with interest a brief blurb on how scientists have developed a method for making human-based gelatin which, apparnetly, can become a substitute for animal-based gelatin. I wonder if this will confuse vegetarians. Will the first colour be green? And most importantly, will they brand it Soylent? Trying to think of a good Bill Cosby joke but have given up.

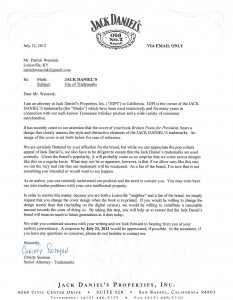

a refreshing c&d letter

That’s “cease and desist” for you non-lawyer types out there. Not often that I use the words “cease and desist” and “refreshing” in the same sentence. But completely appropriate for this story that highlights a trademark infringement cease and desist letter sent out by Jack Daniel’s trademark lawyer that is actually civil and polite.

I think it’s a good illustration that lawyers don’t necessarily need to engage in overbearing, high-handed or brow-beating tactics all the time to protect the interests of their clients. Compare and contrast this, for example, to the approach taken by one Charles Carreon.

Congratulations Christy Susman – I think you’ve earned a lot of fans (and prospective clients). And deservedly so. And who knows, maybe I’ll pick up a bottle of Jack on the way home. It sounds a lot tastier.

More coverage in boingboing, Mashable and The Atlantic.

Tip o’ the fedora to Jeanette Lee.