I was in the middle of writing yet another half-finished post (this one on Groupon, in case you were wondering) when I was distracted by a tweet from Barry Sookman on how a court determined that Wikipedia is not a legal authority in US courts, which then pointed to a brief blog entry written by Peter Vogels. In it, he concludes with this statement:

Even though the Smithsonian Institution is now teaming up with Wikipedia that does not validate Wikipedia postings for the Courts. As time moves on Wikipedia may be a reliable source for the Courts, but when is still unpredictable.

which I interpreted as disappointment with the court’s ruling, at least as far as Wikipedia goes. This piqued my interest a bit, so I took at look at the order (PDF – which Mr. Vogels was kind enough to link to in his entry). The operative paragraph was set out in the following footnote in the order:

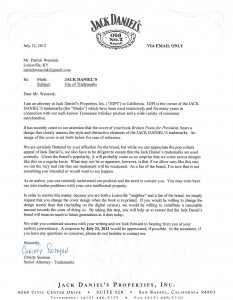

4The court notes here that defense counsel appears to have cobbled much of his statementof the law governing ineffective assistance of counsel claims by cutting and pasting, without citation, from the Wikipedia web site. Compare Supplemental to Motion for New Trial (DN 199)at 18–19 with http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Strickland_v._Washington (last visited Feb. 9, 2011).The court reminds counsel that such cutting and pasting, without attribution, is plagiarism. Thecourt also brings to counsel’s attention Rule 8.4 of the Kentucky Rules of Professional Conduct, which states that it is professional misconduct for an attorney to “engage in conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit or misrepresentation.” SCR 3.130(c). See also In re Burghoff, 374 B.R.681 (Bankr. N.D. Iowa 2007) (holding that counsel’s plagiarism violated identical provision of Iowa Rules of Professional Conduct). Finally, the court reminds counsel that Wikipedia is not an acceptable source of legal authority in the United States District Courts.

This, in turn, was a footnote to the following sentence in the order:

The defendant claims that she must be granted a new trial because the representation she received was so deficient as to violate the Sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution.4

I’m not sure the statement of the court above is necessarily as unfortunate as it sounds. Legal authority is usually used to describe “reporters” – specific publications that publish court decisions. Some are “official”, as in they are approved in some way by the courts, while others, which are still accepted by the courts, are not. These reporters, as far as I am aware, take great care to ensure that decisions are published completely and accurately. They are typically well known by lawyers and judges, so that anyone given a reference to a particular case using a particular citation will be assured that it will be identical, down to the page, of anyone else looking at that citation. For example, R. v. Big M Drug Mart Ltd., [1985] 1 S.C.R. 295 will allow any lawyer or judge to look up the case described in a specific reporter.

If I’m interpreting the above correctly, the judge seems to be suggesting that the lawyer in question basically tried to rip-off arguments in another case without acknowledging that they came from another case (or rather the Wikipedia entry for the case) – at least for all of the footnote other than the last sentence.

That last sentence, however, I think speaks only to legal authority in the sense I’ve described above. Or at least I hope it does, because that would be a sensible thing to say – after all, the full text of decisions are not published on Wikipedia but rather summaries which are editable by users. And when it comes to citing past decisions as the basis for coming to a new judicial decision, it is probably important to have some degree of reliability, immutability and consistency for your sources. Or perhaps stated simply, lawyers shouldn’t be providing a link to Wikipedia when they’re citing a case as precedent – they should be citing authoritative reporters.

This should be distinguished, I think, from more general use of Wikipedia by the courts to refer to factual matters, which an article in the New York Times summarized the current perspectives quite well. The article in particular noted a case where a US court had rejected references to Wikipedia:

When a court-appointed special master last year rejected the claim of an Alabama couple that their daughter had suffered seizures after a vaccination, she explained her decision in part by referring to material from articles in Wikipedia, the collaborative online encyclopedia.

The reaction from the court above her, the United States Court of Federal Claims, was direct: the materials “culled from the Internet do not — at least on their face — meet” standards of reliability. The court reversed her decision.

Oddly, to cite the “pervasive, and for our purposes, disturbing series of disclaimers” concerning the site’s accuracy, the same Court of Federal Claims relied on an article called “Researching With Wikipedia” found — where else? — on Wikipedia. (The family has reached a settlement, their lawyer said.)

The article does go on, however, to identify a number of instances where Wikipedia had been accepted by other courts, sometimes for rather important facts, which has been criticized by some:

In a recent letter to The New York Law Journal, Kenneth H. Ryesky, a tax lawyer who teaches at Queens College and Yeshiva University, took exception to the practice, writing that “citation of an inherently unstable source such as Wikipedia can undermine the foundation not only of the judicial opinion in which Wikipedia is cited, but of the future briefs and judicial opinions which in turn use that judicial opinion as authority.”

while others have been less harsh:

For now, Professor Gillers said, Wikipedia is best used for “soft facts” that are not central to the reasoning of a decision. All of which leads to the question, if a fact isn’t central to a judge’s ruling, why include it?

“Because you want your opinion to be readable,” said Professor Gillers. “You want to apply context. Judges will try to set the stage. There are background facts. You don’t have to include them. They are not determinitive. But they help the reader appreciate the context.”

I guess my point in all of the above is that I’d be inclined to agree that Wikipedia shouldn’t be used at all to cite legal authority (assuming of course I’m properly interpreting what the court meant), without of course discounting the desirability of perhaps replacing (or supplementing) the rather antiquated, primarily paper-oriented system of legal authority with more modern, internet-accessible means of publication. Conversely, I would think that references to Wikipedia for factual matters should perhaps be a bit more flexible, and I don’t think this particular order rules that possibility out.